As a university instructor (college teacher), I have learned that some students fail. They don’t show up to class, or they can’t find a way to stay motivated, or their time management skills are lacking. Sometimes they need a job and their shifts are during my class. There are so many reasons, but every semester a few fail. It was hard in the beginning not to take this personally, but I don’t anymore. I understand that it just might not be the right time for them to take this on. I can email them, reach out after class, and try to include their interests in my lesson plans, but I can’t take the class for them. Sometimes there is a better lesson in failure than in success.

I know that as a teacher, but I don’t know that as a mother.

I know that as a teacher, but I don’t know that as a mother.

As a mother, I don’t want to fail, ever.

As a mother, my time management skills go out the window. I spend thirty minutes trying to get a toddler to eat two bites of yogurt. I go three days without showering. I spend over an hour on bedtime, because he just doesn’t feel safe in his big boy bed yet. I. Just. Can’t. Even.

As a mother, I research all the safety and baby-proofing information. I do my homework and I find conflicting answers. Locking your toddler in their room is bad because they can’t escape if there’s a fire. Locking your toddler in their room is good because firefighters need to know exactly where they are in a fire, and you won’t be searching a house full of smoke to find them. Buy decals to put on their windows so firefighters can locate them. What is best? I don’t know. I don’t know. I spent six years in college, and have three degrees related to critical thinking. Why can’t I choose?

I have anxiety about mothering.

I can talk in front of big groups of students all day long. I can talk to them one-on-one. I can go to meetings, nod, and offer my own ideas. I feel great about public speaking. But when I’m driving sometimes I have to pull over, I’m so overcome with fear. My child is outside of me in this big, scary world. The lines from Maggie Smith’s “Good Bones” radiate throughout my body: “For every loved child, a child broken, bagged/ sunk in a lake. Life is short and the world/ is at least half terrible, and for every kind/ stranger, there is one who would break you/ though I keep this from my children.”

I can talk in front of big groups of students all day long. I can talk to them one-on-one. I can go to meetings, nod, and offer my own ideas. I feel great about public speaking. But when I’m driving sometimes I have to pull over, I’m so overcome with fear. My child is outside of me in this big, scary world. The lines from Maggie Smith’s “Good Bones” radiate throughout my body: “For every loved child, a child broken, bagged/ sunk in a lake. Life is short and the world/ is at least half terrible, and for every kind/ stranger, there is one who would break you/ though I keep this from my children.”

As a teacher, I tell my students that the stakes should be high in their papers. The call to action should be doable, but also meaningful. As a mom, the stakes are too high. When my son jumped out of his crib and had to get an arm cast, I was convinced that our crib had been lowered all the way, but it wasn’t. We didn’t lower it, and he could have been injured even worse. How could this happen? Every year, children are left in cars and they die. People accidentally run over children and they die. Children find guns and they die. The stakes are too high.

As a teacher, I tell my students to write a draft, then another draft, and then more drafts. At some point, you just have to turn it in, but you don’t have to consider it done.

I have each day with this child. Some days are good, and some days are bad. At some point, I will have to turn him out into this world, but I will never consider him done.

As a teacher, I step back and observe. I know my students grow by making mistakes, and I want them to find their own path of correction. As a teacher, I invite people into my class to observe me. I need notes on how to improve. As a mom, I’m so scared of everyone watching all the things I’m doing wrong. Don’t look at my screaming toddler who refuses to sit in the cart. Please, don’t comment on the fact that both our clothes are covered in chalk. You can’t imagine. At least I am here buying groceries. Don’t comment on my cheese puffs. No, I don’t know what a puff is, ok. It’s a food product, not a food, I know that much.

As a teacher, I know the writing process is non-linear. You might research, and then go back and refine your question, and then re-write your thesis. My toddler is linear though. I can’t tell him to forget the word I said yesterday. I can’t go back to when he was an infant and breastfeed him longer. I go back and back in my mind, but I can’t lower his crib any sooner than I remembered to do it.

As a teacher, I know the writing process is non-linear. You might research, and then go back and refine your question, and then re-write your thesis. My toddler is linear though. I can’t tell him to forget the word I said yesterday. I can’t go back to when he was an infant and breastfeed him longer. I go back and back in my mind, but I can’t lower his crib any sooner than I remembered to do it.

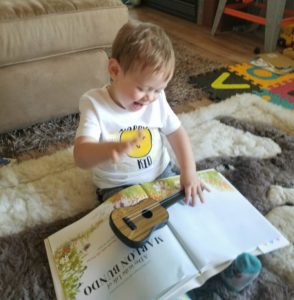

I tell my students in the beginning that most folks who fail the class, fail because they just quit showing up. So, I show up. I show up at 3:00 a.m. I give up on putting him back to bed, so he sleeps next to me, but I’m there. I show up for the wake-up time that inexplicably comes at 5:00 a.m. now. I show up in the muddy backyard when he wants to play in the rain. I show up when he’s sick at daycare. I show up to explain the difference between poop and the picture of coal in a book about trains. I show up at church, and at open gym play, and swim lessons.

I tell my students that the most successful people aren’t necessarily the most talented ones. They just are the ones who put in the effort and plodded away every day until they reached their goals. And yet, there’s Philip Levine in my heart; “You know what work is—if you’re/ old enough to read this you know what/ work is, although you may not do it./Forget you. This is about waiting.” Mothering is more than work. It’s more complicated than work. It’s also a waiting thing. It is boring and normal, and often there is nothing new to report.

I am not the teacher in my mother-child relationship.

I am the student. My child teaches me to slow down and see, “Uppies, up, a bird.” He teaches me to mess-make. He requires me to learn patience and awareness. I pay more attention to breath now, to my body, as he takes his on and pushes it further. “Jump, jump,” he says, but he can’t do it yet. He just keeps trying. I just keep trying, too.